Reading the Lectionary with African American Women Interpreters

Sunday, May 18, 2025

Weekly Lectionary Spotlight: Phillis Wheatley reads Psalms 148

“ARISE, my soul, on wings enraptured, rise; To praise the monarch of the earth and skies, Whose goodness and beneficence appear… Adored for ever be the God unseen…Adored the God that whirls surrounding spheres…”

~ Phillis Wheatley

Sponsored By:

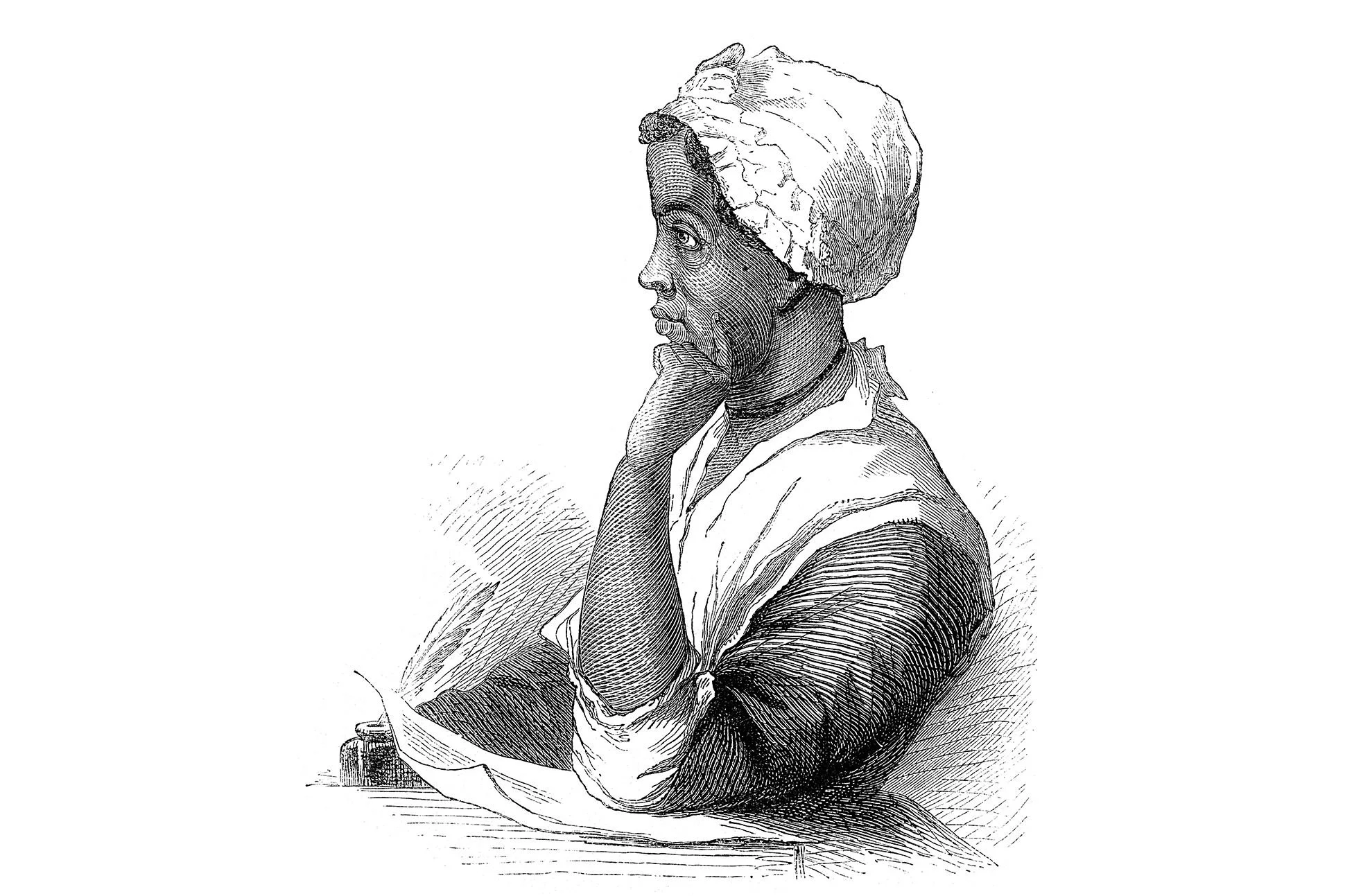

Bio: Phillis Wheatley was born around 1753 in West Africa and was torn from her home as a child, arriving in Boston aboard a slave ship. In the Wheatley household, she startled her captors with her brilliance, scribbling marks her mistress called nonsense; though some now believe she was writing in Arabic, the language of her earliest years. By her teens, Phillis was crafting poetry in English and Latin, her words vaulting over every boundary set before her. In 1773, she became the first Black American to publish a book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, and her “On Being Brought from Africa to America” still stirs with its grace and quiet strength. Wheatley died at just 31, but her voice endures. Her voice is proof that even when uprooted and unheard, a single soul can leave an inheritance of hope and courage for generations she would never see.

Phillis Wheatley

(1753-1784)

Bible Passage (NRSVue): “Praise the LORD! Praise the LORD from the heavens; praise him in the heights! Kings of the earth and all peoples, princes and all rulers of the earth! Young men and women alike, old and young together! Let them praise the name of the LORD, for his name alone is exalted; his glory is above earth and heaven.” (Psalms 148:1, 11-13)

Her Interpretation: Imagine a dawn where the sun doesn’t just rise—it curtsies. Where mountains don’t merely loom but glow, their peaks humming hymns. This is the universe depicted in Phillis Wheatley’s “Thoughts on the Works of Providence,” a psalm reborn with power that changes our lives. Once sung by stars and storms, the biblical call for creation’s praise becomes a manifesto of mercy in her hands. Wheatley, a poet who rose from bondage to celestial visions, traces God’s order in the sun’s “blazing obedience,” the mountains’ “radiant surrender,” and the galaxies’ silent dance. “The monarch of the day I might behold,” she writes, gazing at a sun stretching “miles twice forty millions”—a fusion of childlike awe and a scholar’s eye. Her faith isn’t merely doctrine. It's a moonlit epiphany, etched in alpine slopes and cosmic whispers. When she breathes, “What Power, what Wisdom and what Goodness shine!” she’s not just quoting scripture—she’s tracing God’s signature in every speck of stardust.

Dr. Shively’s Reflection: Imagine a voice not echoing from pulpits or palaces but rising from the hold of a slave ship. It is a voice carrying the resilience of a people. In a Boston kitchen, Phillis Wheatley’s hands, marked by the memory of shackles, poured ink onto parchment. With over 145 poems to her name (though only 65 remain), Wheatley wielded the Psalms as instruments of liberation. Psalm 148’s call for “mountains and all hills” to praise God became, in her hands, not just a ritual but a quiet rebellion. Denied humanity by law, she answered the psalmist with, “Adored forever be the God unseen,” rooting her identity not in bondage but in a cosmic choir where even the “radiant gold” of the hills testified to justice. Her poetry, a powerful tool, sings with the struggles and hopes of those pushed to the edges, souls whose stories are often left out of the grand halls and history books, but who refuse to be silenced. Her spirituality burned with boldness! She refused to let the world that called her property define her soul’s reach. In reimagining Psalm 148, she slipped her people into the sacred chorus, asking with every line, What of the chained, the cast aside, the ones whose names are spoken in whispers? Do we not also sing? This reimagining was not just a literary exercise. Still, a sacred act of reclaiming dignity and belonging for those history tried to erase. Her “gentle hand of Providence” was no passive comfort. It was a challenge flung at a nation that mistook power for holiness. Every star she named, every storm she called “Triumphant o’er the winds,” reflected the endurance and hope of those who walk the long-shadowed road: Black and brown bodies, women, Indigenous kin, newcomers, the differently abled, all who have lived on the underside of someone else’s empire.

Points for Preaching & Study

Greetings!

Welcome to Dr. Shively Smith's Digital Gallery of Interpretation for the 2025 Easter and Pentecost Lectionary season. This gallery celebrates the unique and rich legacy of 19th-century African American women writers (circa 1789–1899). It explores how their distinct perspectives can inform our application of the Bible in 2025. Each of these women was a pioneering interpreter of Scripture, utilizing the prevalent translation of their time, the King James Version (KJV).

For more information, listen to Dr. Shively Smith explain her digital Lectionary.

This digital interpretation gallery, designed for the Easter and Pentecost seasons in 2025, is a valuable resource for enhancing sermon preparation and personal Bible study. It is suitable for preachers, teachers, students, and laypeople alike. Sponsored by the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship, Dr. Shively’s gallery invites you to actively explore the contributions of African American women from the 1800s as guides for biblical interpretation.

The guiding question(s) below will help you compare the quotations of 19th-century African American women writers with the specific Bible passages used each Sunday.

Easter Questions to Ponder: